The hidden vineyard in Ongar, Essex |

Doors Open and Close...

The hidden vineyard in Ongar, Essex |

We visited Chris’ Aunt and Uncle, Iris and Ted, on more than one occasion. The above photos show us with them in the vineyard they and others tended in Ongar, Essex.

During June of 1992 I wrote a letter to Glenn White at QMC regarding a planned meeting I’d agreed to attend in Japan during July. The meeting was to foster various joint UK-Japan research and development on projects like creating new types of solid-state mm-wave oscillator. However by the middle of 1992 I was having serious anxiety attacks, worried about being away from Chris and home for any period of time. These came and went, depending on her own condition. Sometimes she would be OK, and I’d be happy to travel without her and be away for a few days. At other times neither of us could travel. For me, the added worry was becoming that I might agree to go away and that people would make arrangements, spend money, etc, only for me to fail to go at the last moment. Thus I would get into a ‘negative feedback loop’ of worrying so much about the likelihood that I’d not be able to go that this in itself made me feel too ill to travel!

Fortunately, Chris and I could still usually travel together, provided we were both OK. But I decided it was time I was honest with Glenn and others, and withdraw early, rather than risk being a ‘no show’ at the last moment. This was quite difficult to explain because of one of the ironies of mental illness is that other people may only see you when you are OK, not when you are unwell. They don’t see what you are like when the illness prevents them from seeing you! Hence your behaviour seems baffling or absurd. But for the person affected it can be as real and disabling as a broken leg.

In reality, I was having doubts that much would come from my taking the trip anyway. I’d sent a number of faxes and letters to the Japanese researcher who had said when in the UK that he could let us have some novel devices. But I’d had no real replies, and no devices. So I suspected this particular possibility wasn’t going to come to bear fruit anyway. Without that I wasn’t sure my attending would contribute a great deal. However I was disappointed by feeling unable to go to see what could be achieved. And did regret letting other people down.

1992 Andy's Wedding |

In July 1992 Andy Harvey married Monika in the church on The Scores in St Andrews. The above appeared in the St Andrews Citizen local newspaper shortly afterwards.

On the 12th of July 1992 I wrote a letter to Pauline Pickering of the Sir John Barbirolli Society, asking to become a member. I’d collected a few LPs and CDs of Barbirolli conducting various works, and enjoyed them. I knew a society had existed because I’d seen some details mentioned on an old LP they had issued. But I didn’t know if they were still in existence, or how to contact them until I read a mention of them in a copy of “Classic CD” magazine that gave Pauline’s name and address. So I wrote to try and make contact. Alas, I didn’t get any reply until somewhat later – in 1994! But I did then join and have remained a member.

By 1992 I had become an enthusiastic user of the computer systems designed and sold by the UK maker, Acorn. When their ‘Archimedes’ systems were launched I was very impressed by them – both as a desktop machine running the ‘RISC OS’(RO) operating system on the early ARM processors, and when interfaced to laboratory instruments to control them and collect/analyse data.

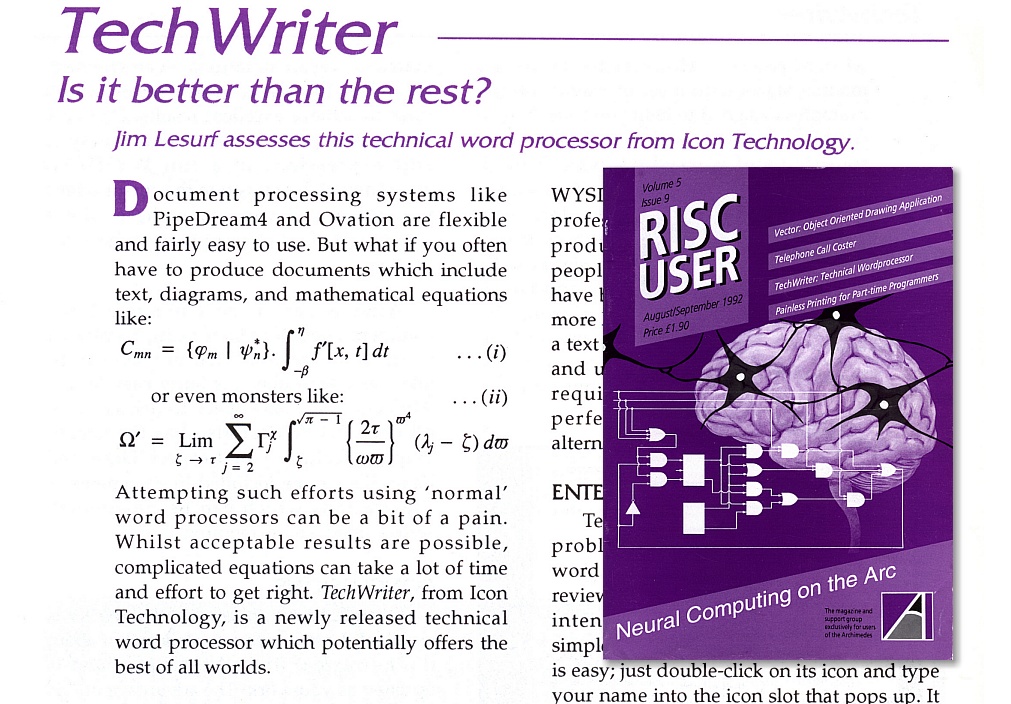

During the summer I was sent a copy of a new RO application called !TechWriter and invited by the editor of RISC User magazine to review it for them. I can’t now recall exactly why he asked me, but it might have been because I’d written a letter to the magazine a few months previously about some software I sent in which readers might find useful. Quite simply, !TechWriter took my use of the Acorn machines to a higher level! I not only reviewed it, I decided that it was my ‘killer app’ for using RO. i.e. the program that made RO the only choice for me when it came to writing documents, etc. It had a revolutionary effect on my working life from then onwards.

As with many scientists, engineers, etc, I frequently needed to write reports, papers, etc, that included complex technical content. In particular I needed to include diagrams and all kinds of equations. Up until summer 1992 I’d had to develop my own DIY ways to include the required maths and diagrams in documents. I’d developed a system I’d called ‘DreamPrinter’ to do this, and used it to write the manuscript for my first textbook, and many early versions of my lecture notes, reports, etc. However although this worked it was a real fiddle to use, and didn’t give high-quality results.

!TechWriter Review |

!TechWriter was in another league. It allowed me to type in ‘live’ equations I could re-edit, and which appeared - on-screen and when printed – in a superbly displayed layout that matched all the internationally laid down standards for how equations, etc, should be printed. What it displayed on-screen accurately showed how the printed version would look like. It was also very easy to use. It stood head and shoulders over any other document processor I’d ever encountered on any computer platform. I therefore wrote a very positive review. I also found over the following months and years that its developers and owners were both very friendly and helpful. As a result from then on I exchanged countless letters, then emails, with them. They welcomed feedback and continually improved !TechWriter over the following years. I’ve long since lost count of how many documents I’ve written using it. Books, journal papers, reports, etc... and, yes, I wrote this webpage using it - and hundreds of other webpages over the decades.

During August I wrote a letter for Graham Smith to use as a Reference when applying for jobs at other universities. At the time his funding was via a 2-year project to develop a sideband noise measurement system for the NPL’s Standards Section, based at Defence Research Agency, Malvern. This funding would come to an end in November 1992. We were attempting to obtain a new research grant which would fund his work for at least three years. However at the time it was by no means certain we would succeed. He enjoyed working at St Andrews, but obviously had to consider going elsewhere. I wrote a very positive reference to make clear that he was an outstanding researcher, but in addition I included the following:

| “I strongly recommend Graham for any research post. Frankly, if I can find funding, I will attempt to persuade him to stay with us at St. Andrews. I believe that, if it were not for the grim state of University funding in the UK, Graham would by now have been given a permanent staff position here. However, given the state of the UK I must sadly agree that he is wise to look to a wider horizon for his future career. I have no doubt that he will make a success of whatever he does, and will prove an asset to any employer.” |

Fortunately for me and St Andrews University, we managed to keep Graham, via securing another year of funding and this led to the ‘TopSpin’ project...

During this period we were funded via a variety of medium/short term payments from different source. For example, during August both Mike Leeson and Malcolm Robertson were funded via contracts from the Defence Research Agency (DRA) at Farnborough for items of work. Where possible, though, we used these as ‘fillers’ in between projects that were funded for longer periods to give the people involved more security regarding their income, etc.

On the 22nd of August I wrote a letter to Council’s water department regarding the poor quality of the tapwater. For some weeks it had emerged from the taps with a muddy brown colour and an ‘over-chlorinated weak tea’ sort of taste and smell. It also left a coating on a glass or cup if allowed to stand for a few hours. I – and others – were concerned that it might not be fit to drink. An official did visit and take away a sample, agreeing that it would be examined. But when I asked later on they said the sample was unsatisfactory for being tested, so had been discarded! We never did any real explanation, just a default presumption that the water was ‘safe’ because no-one was prepared to say it wasn’t!

Shortly after this, we had a new kitchen installed. Chris had been wanting to replace our old kitchen units, etc, for some time. The work was carried out by a local firm called “Osprey Kitchens”. I was impressed by the quality of the wooden doors, etc, they made for their units, and they did an excellent job of removing the old units and fitting the new ones. Part of this involved moving the (gas) cooker from being immediately to the left of the back door to being further away, to the right. This solved some problems caused by the old positioning. There, opening the back door might let in a breeze that blew out the flames, and it was sometimes so bright you couldn’t see if the gas was lit or not! So the new location was much safer as well as being more convenient.

During October I wrote another review for Risc User magazine. This was reporting on the ‘Floptical Drive’ devices which were being sold as a high-capacity alternative to the then-common ‘floppy discs’ people used to store and convey computer data. At the time typical ‘floppies’ could hold the order of about a megabyte of data. The ‘flopticals’ used a disc of similar size and shape, but employed an optical sensor to system to enable much more accurate positioning of the read/write head in the drive. As a result, they could pack around twenty times as much data onto a disc. The ones I bought and used worked very well. But the system never really caught on, so both discs and drives ceased to be available a few years later. Nice idea, but it failed as a commercial proposition.

That month a group of people from the SERC (Science and Engineering Research Council) visited St Andrews and I was able to present some highlights of our work. This let me point out that, for example, the sideband noise measurement system that Graham had developed was of use for UK defence and industry and provided measurements that were 4 orders of magnitude (i.e. 10,000 times more sensitive) than any commercial alternatives.

I also arranged that GEC would fund Graham for a few months to work on Gunn diodes/oscillators and ensure he was paid as we worked to get him a longer-term position. Prof. Peter Riedi, Graham, and myself had submitted an SERC grant request to build a high-performance ESR (Electron Spin Resonance) instrument. If funded, this project would run for three years and employ Graham to design and develop/run the instrument. But we needed to ensure he had some income whilst we waited for the SERC to decide to fund this project or not.

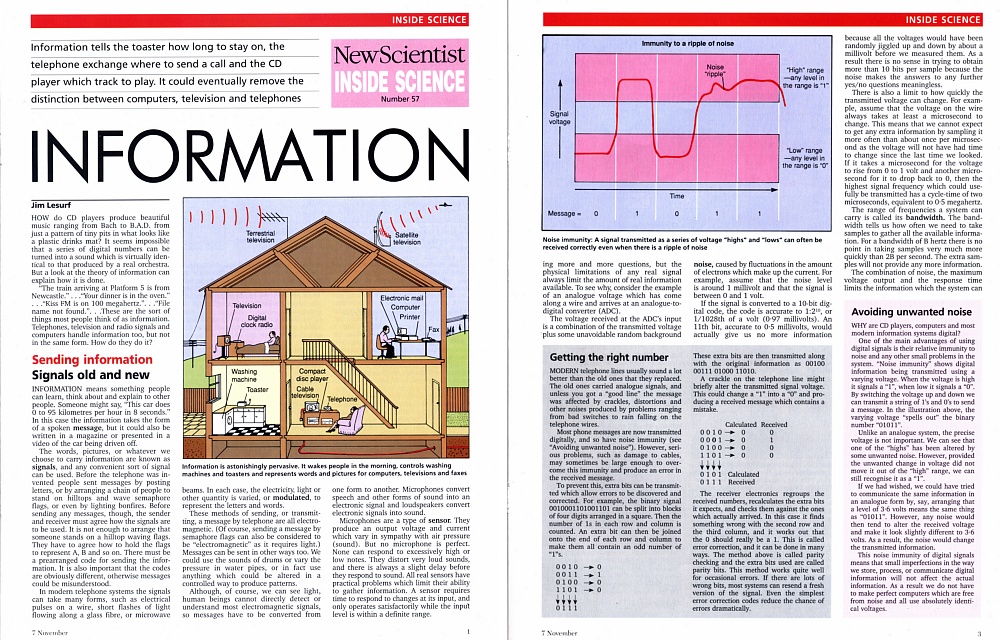

1992 Nov 7th Inside science - info |

In November 1992 New Scientist published another “Inside Science” pull-out which they had asked me to write for them. This one went into the basics of information theory and how data can be represented and used in ‘digital’ forms.

Mike Leeson’s PhD viva was held on the 28th of October 1992. As usual, the viva was in the morning, he passed, and we went to have lunch at The Parklands Hotel. His internal examiner was Prof. Arthur Maitland. Malcolm Robertson’s viva also took place during October, and also went smoothly along the same path.

During 1992 the MM-Wave Group continued to sell around half a dozen Gunn oscillators per year, and work in conjunction with GEC on assessing the performance of the diodes they were able to supply. As a result we could routinely build and supply 70 - 120 GHz tunable oscillators to various research labs, etc. One of these was purchased by Kent University to provide local oscillator power for a receiver they were building for the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope. Another was sold to British Aerospace.

Darrell Smith had been able to operate a liquid Helium cooled InSb oscillator that gave output at 900GHz – albeit at a very low power level. We had hoped this could be developed into a reliable source of local oscillator in the higher frequency region above that which the Gunn oscillators could provide. Unfortunately that line of experiment eventually proved unfruitful because we were unable to find a way to reliably make cooled InSb oscillators that would deliver useful output.

At the end of 1992 Glenn White visited St Andrews to discuss work and exchange some gossip. This visit, and a Christmas letter from Ian and Chris Robson, told me that they were moving to Hawai’i. Ian would now be in charge of the UK telescopes there. I wrote a reply to Ian and Chris on the 17th Jan 1993. This wished Chris luck with her intent to juggle being in Hawai’i with also keeping a job in “Human Resources” going here in the UK! I also suspected that Ian’s job in Hawai’i would be a really difficult one given the internal politics of JCMT, ROE, etc, at the time. I added that:

|

Things here stagger on as usual. The Physics dept. got a ‘grade3’ (must try harder) in its UFC (or whatever name they now have) annual report card. The problem is that we are what has been dubbed a ‘tadpole’ department. We have a good research ‘head’ coupled to a poor ‘tail’. Up until now, everyone in the department has been expected to contribute about equally in teaching, research, and admin. The central support funding and duties have been doled out on a fairly egalitarian (or ‘buggin's turn’) basis. This is now to change. In future staff are going to be divided into research-active and research-dormant. The research-active ones will get the gravy and the research-dormant ones will be expected to take on a greater fraction of the teaching/admin work.

In the abstract I don't really like this kind of arrangement since it means that potentially good researchers may become stifled under an excessive teaching load before they can prove their worth. Also — as the Japanese say, “Even monkeys fall out of trees” — i.e. even good research workers can go through a few bum years when they can't get support. However, despite my dislike for this divisive approach I can at least comfort myself with the fact that I and the mm-wave group here are classed as research-active. We continue to be fortunate enough to bring in support from various non-SERC sources. With luck I can avoid falling out of the tree!... |

The day before I wrote the letter, I was visited by a BBC journalist. He wanted to interview me for a radio item about digital audio, Audio CDs, etc. As a result I guess I became ‘famous’ in the Andy Warhol sense when my voice was heard on BBC Radio Scotland for about 30 seconds!

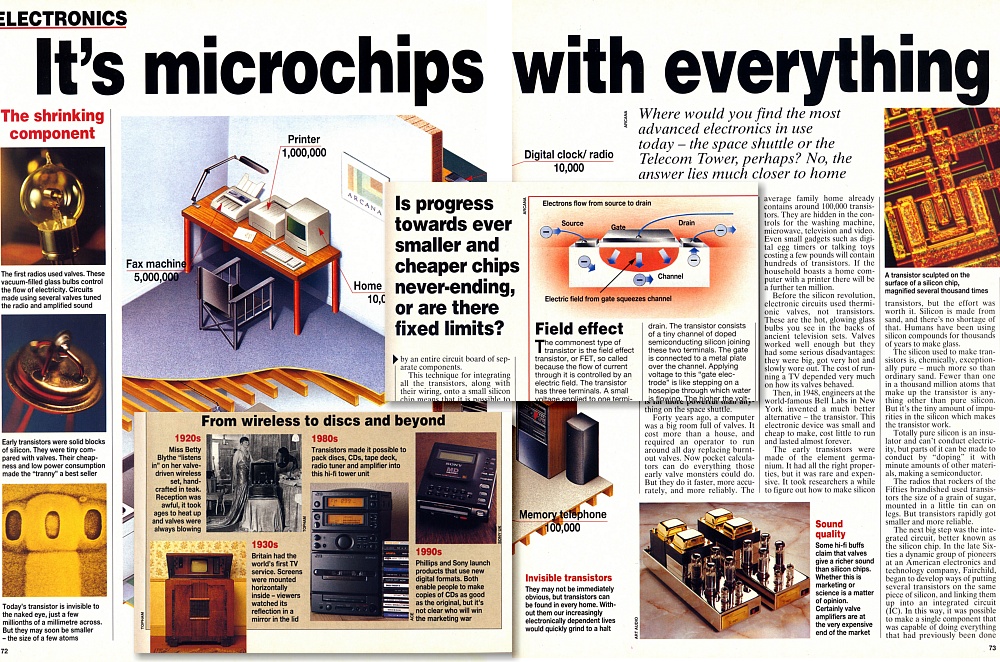

1993 March Focus - Microchips |

Nina Hall, the Editor who I’d worked with at New Scientist decided to move to a new magazine called ‘Focus’. This was a glossier, and was aimed at a wider audience. Having moved, she got me to write some items for the them. The first article of these was on microchips and their uses. It appeared in their March 1993 issue...

1993 Apr Focus - paperless books |

...and was followed in their April issue with another article I – this time on ‘paperless books’. The idea at the time was to release books in the form of a ’mini CD’ which carried the data. This could then be read either by desktop computers or by specially designed portable devices that would display the printed book’s pages, etc. At the time the idea seemed a good one to some technologists. But it never really took off, so reading books using a personal device had to wait until a later generation of mobile devices made it easy to read books from a screen without the need for a disc to carry the data.

During April I also decided to join the Audio Engineering Society. This was something I’d been meaning to do for many years but not got around to.

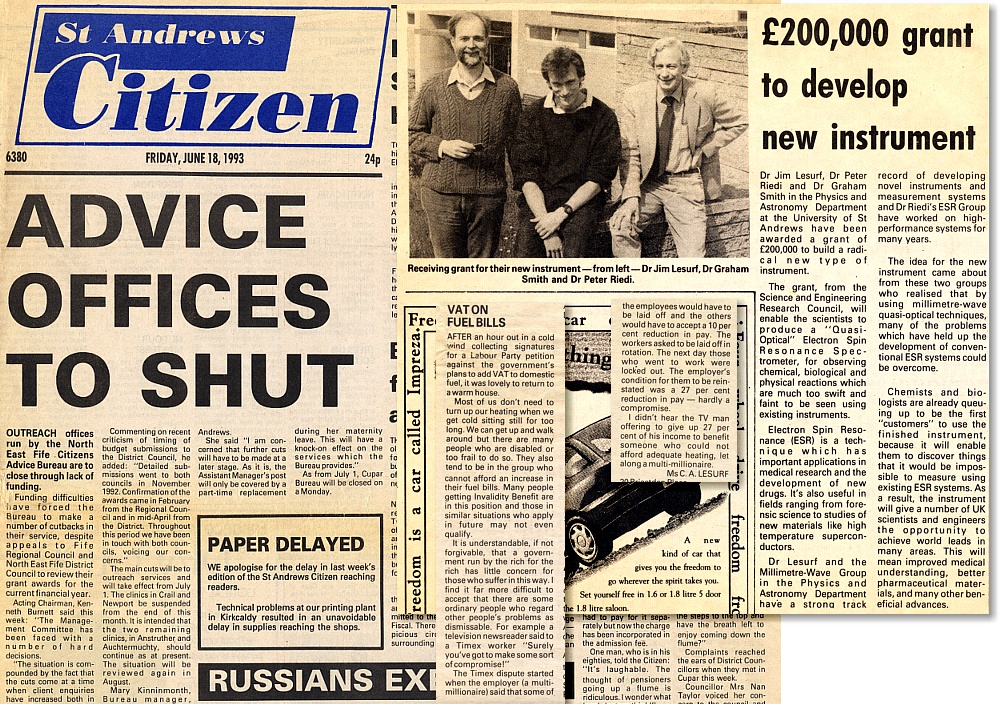

1993 Jun Citizen CAB + letter + grant |

The issue of The St Andrews Citizen that appeared on the 18th of June 1993 contained three separate items which mattered to Chris and myself. The headline article on the front page announced what we’d feared and expected for some time. Fife Council were reducing the amount of support for the CAB, and offices would be closing. This was part of an on-going withdrawal of support. Chris was distressed by this for two reasons. On a personal level, she’d been acting as a helper/advisor at the St Andrews CAB for a number of years. When feeling OK she would go and work two or three days a week, seeing people and helping them with their problems. This allowed her to do work she felt was useful and worthwhile and overcome the depression felt as a consequence of no-one being willing to give her a paid job because of her epilepsy. As a result, helping others in this way also helped her – and me – quite a lot. More generally, she and the other CAB workers could see the relentless increase in the number of people struggling with debt. Even in a town as apparently prosperous as St Andrews, there was an increasingly serious problem with people falling into debt due to unemployment, etc. It angered her that this was happening and that the Council’s behaviour was degrading the provision of support for many people.

The public reasons the Council gave for their behaviour was that they were short of funds. This was true, but having both been in the Labour Party for some years in the past we knew that the real reasons were somewhat different, and more political. During the 1980’s strike by coal miners Fife Regional Council had set up various ways to try and help the miners and their families to cope with not getting any income. At the time Chris and I also tried to help, campaigning and going out with collecting buckets to gather donations for the miners. One result of this period was that the Council set up a ‘Rights Office Fife’ to help miners and their family know how to claim what they were entitled to in terms of welfare benefits, etc.

However having done this, in later years a view started to form in the mind of some councillors based on comparing the Council run ‘Rights Offices’ with the CABs. The key differences were that the CABs were independent of the Council, despite being given Council funding and support. They also covered all kinds of help, for those in ‘prosperous’ (which might not vote Labour) as well as ‘poor’ areas (which did). So the question arose, “Why fund a body we can’t control or tell where to put their effort when we can run our own and control what it does or where it spends the money we give it?”

The result was a ‘death by a thousand cuts’ for the independent CABs in Fife, and their replacement by a Citizen’s Rights and Advice, Fife’ (CARF) set of offices instead. This was implemented gradually over a period of some years. The concerns arising from this were repeatedly explained by the CAB supporters, but were dismissed. The main problem was that the CAB could be seen to be truly ‘independent’. Hence any member of the public (or a council employee/contractor) who wanted help with a problem due to the way the Council treated them could seek help from the CAB without having to fear it would be refused, limited, or reported to the Council as their paymasters / controllers. Provision could also be based on the scale of need, and avoid the risk of it being directed into areas which most suited the Council. This was at least a serious issue of perception even if in reality all was being properly run. However during the 1990s the provision for the CABs was gradually reduced and morphed into CARF. Ultimately, the St Andrews CAB closed. Curiously, despite previous claims by the Council that the property wasn’t worth maintaining, it remains in use to this day...

By chance, the second item in that issue of The Citizen was a letter from Chris complaining about the impact of a Government plan to introduce VAT on home heating costs upon the poor. The third was, in contrast to the others, excellent news – for me, and for Graham Smith. It announced that we had succeeded in being awarded a significant research grant by SERC. It was a project that had emerged out of a chat over a cup of tea...

When at QMC I’d become used to the way the Physics dept. there ran a ‘tea club’. This meant there was a coffee break in the morning, and a tea break in the afternoon when everyone who wasn’t otherwise engaged could go and sit with other members of the department to have a chat over a cup of tea or coffee. In addition to being a time to relax this was actually very handy as way to find out what other people in the department were doing. As a result, it sometimes allowed one person to provide some useful info that helped another, or to spawn entirely new projects or ideas. So, although to an accountant it might look like wasted time, it could prove very productive. The St Andrews Physics dept. had (and still has) a similar tea/coffee club and times. The main difference there was the view out to be able to see the hills to the north of Dundee.

I tended to ask people about the work they were doing, mainly simply out of curiosity as I often didn’t understand the details. However my central interest was metrology (the science and engineering of measurement, not the weather!). So having found out about what kind of research they were doing I tended to also ask what they would like to measure if the equipment they had could be improved or replaced with something ‘better’. One day I’d had such a conversation with Professor Peter Riedi about his research in ESR (Electron Spin Resonance).

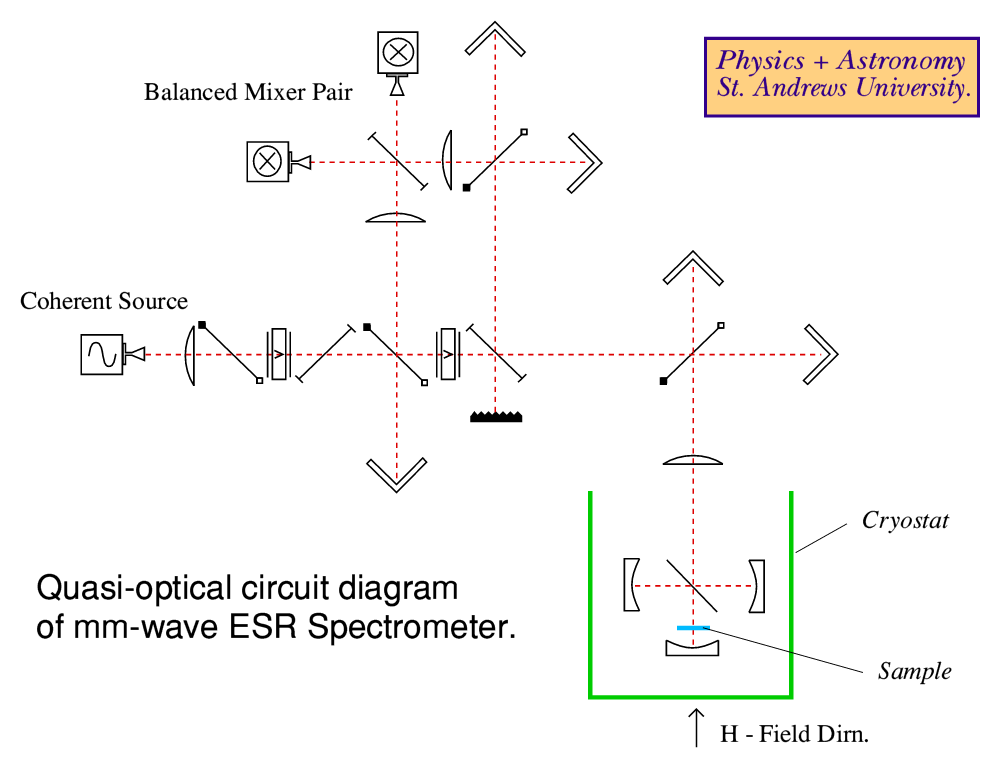

That initial chat lead to more discussions between Peter and myself, and Graham Smith, who became quite interested. The result was that we devised a new ESR system with the potential to make measurements in a significantly improved manner. Up until that time, Peter (and other ESR researchers) tended to use electronics of more conventional kinds, and this often limited their being able to make measurements at very high magnetic fields or high probe frequencies. I quickly realised that by adopting a Quasi-Optical circuit approach those limitations could be bypassed.

|

The above shows an example the kind of QO ‘circuit’ we devised. In principle, this could work from frequencies around 70GHz up into the region well above 300GHz. In practice it was limited only by the available coherent source’s frequency and the strength of the magnetic (H-) field which could be applied to the sample being measured in a cryostat.

A key part of our system was a “secret weapon” which Graham had devised. Not shown on the circuit diagram. The challenge was/is that the sample being measured is cooled to a very low temperature. Some researchers elsewhere were also trying to ‘optically’ couple to such a sample by using a chain of lenses. But each lens tended to lose/reflect some of the mm-wave beam, and degrade the results quite markedly. Graham came up with the idea of using what’s know as a ’corrugated waveguide’. This consisted of a long pipe with a circular cross-section acting as a sort of wavgeguide from the top of the dewer down to the sample arrangement.

However the pipe needed to be quite wide in diameter to minimise signal losses, and had to have a very precisely machined series of circumferential grooves cut into its inner surface. These had to be small, narrow, and very uniform. The pipe also had to be made of stainless steel with a very thin wall, to avoid it conducting too much heat into the cryostat and boiling away all the liquid Helium used to cool the sample. Our secret weapon here was George Radley, the group’s technician. He was able to devise a way to make such a pipe. It was a really outstanding feat of mechanical machining to make it work. Apart from this, the optics used our usual approach of lenses, mirrors, etc.

It was also clear that although we needed to design, develop and operate the system as a challenging project in terms of the physics and engineering, many of the people who’d want to use it to get scientific results would be chemists or biologists. So we wrote an application for a grant on the basis of saying that:

During July I’d written a short letter to ‘Hi Fi World’ magazine, pointing out an error in their ‘explanation’ of how LPCM audio worked. Alas, they went on repeating much the same misunderstanding on other occasions over the following decades, and have seemed impervious to this problem with what they occasionally write. (So in 2008 I wrote a webpage on the topic to try ensure readers would be aware of the issue even if the magazine ignored it. If you are interested the page is linked here: DirtyDigitalDelusions.html)

Chris’s fits and episodes of suicidal depression, anxiety, confusion, etc, continued. One result of this was that her GP and epilepsy consultant kept changing her medication to see if that might help. Alas, this seemed to be pretty much an exercise of ‘darts in the dark’ and ‘try this, it might help’ guesswork. The result was usually various unwanted and unexpected side-effects or added problems that just made things worse overall. During July there was also a serious error in her prescription. The consultant had decided to try her on Gabapentin. But the actual prescription we were given was for three times the intended amount because of a muddle about the dose of the individual tablets. What he had in mind was 300mg taken as three 100mg tablets per day. The prescription as made out was for three 300mg tablets per day!

Fortunately, by then we had both become cautious about changes in medication, so she started off by only taking one tablet per day rather than the prescribed three. This made her feel very drunk and confused, and also serious constipated to the point that she sometimes bled when trying to go to the toilet! She did write to the GP and consultant about this after a few days. The plan at the time was that she would continue to take just one of the new tablets per day (in conjunction with her old medication) until she saw the consultant again in October. But over the next few weeks it became clear that the original prescription for three tablets/day was seriously wrong, and that it was simply too unpleasant to go on taking even one per day. So after a couple of weeks she stopped taking the Gabapentin and just continued with her previous medications. We can only be thankful that she didn’t start off and persist with taking the new drug as prescribed! Sadly, examples like this have over the years been all too common in our experience, and in some cases the consequences were much more severe in later years.

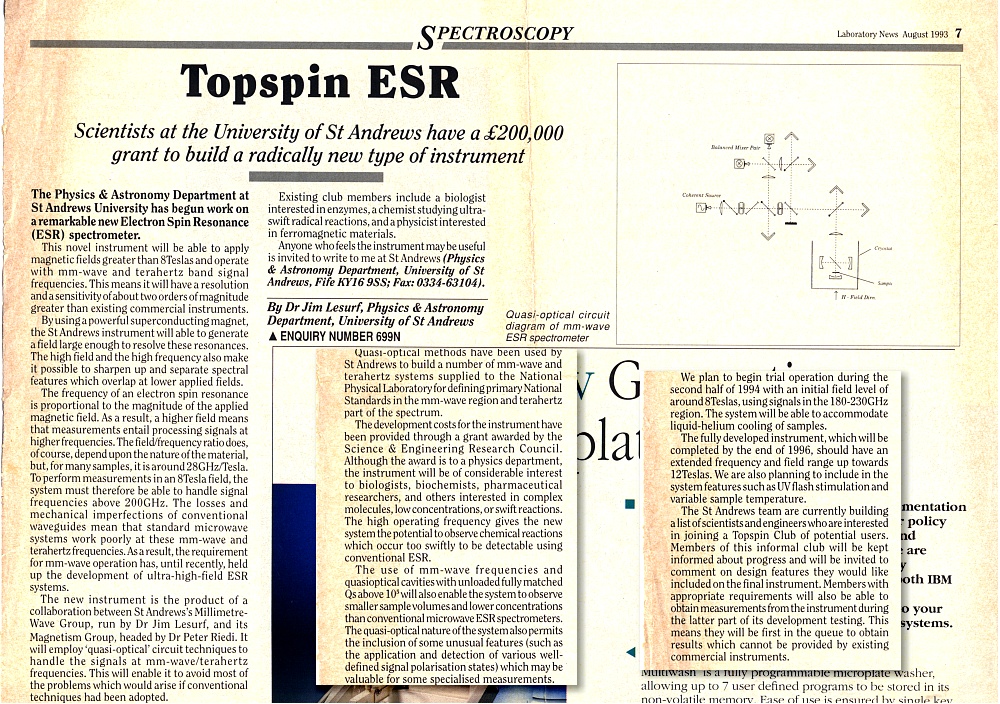

1993 Aug - Lab News and Topspin |

The above shows an announcement I wrote and which then appeared in the ‘Laboratory News’ magazine devoted to describing new research and development equipment. This gave a fuller account of what we were doing and planning in our ESR project than had appeared in The Citizen back in June. We made up the name ‘TopSpin’ for this, and the way it would become accessible to users. It took another 2-3 years before the system was fully in operation. Once built, the instrument became a facility that many researchers queued up to use. And Graham started to advise other groups on how to develop similar systems. Systems based on this are still in use at St Andrews, and provided access for many researchers to obtain measurements on their samples, to move forward science of various kinds.

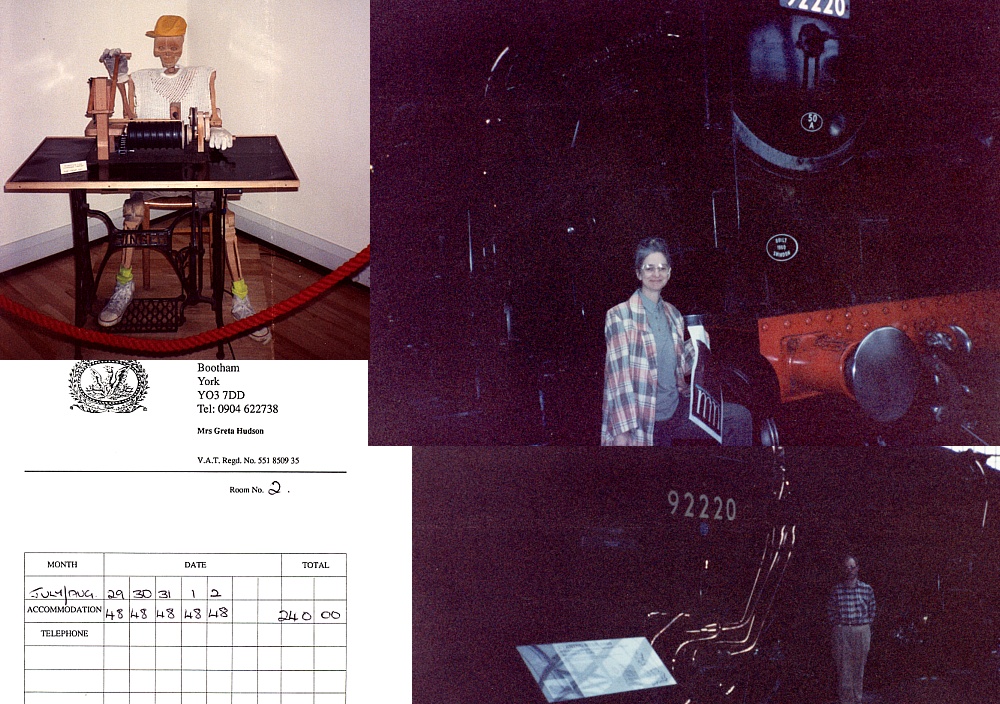

1993 Aug - York |

At the end of August 1993 Chris and I went to York and spent a few days there. I’d visited the city on a previous occasion for a meeting and realised it would be an excellent place to spend some time. In particular, we both have an interest in railways – particularly steam locomotives. So the National Rail Museum was a “must see” place for us. We spent some time at the museum, and I took a number of photos. Alas, I remain a useless photographer. I used a flash attachment with the camera because the main hall of the museum was too dark to simply use natural light. However I had no experience with the way this would mean that more distant objects would appear much darker. In the above images you can see the results. Chris is reasonably well lit when beside the “Evening Star” locomotive, but the actual locomotive is too dark to see clearly. We also visited a small museum of automata. Here my photos came out better because the rooms were reasonably lit and I was more fortunate! One of the perils of the era before digital cameras was that I was unable to see what the photos looked like until weeks afterwards when the prints came back from the chemists. Too late to try again!

When we got back home I wrote a letter to my friend, John Scott, where I described the trip...

|

“We've just got back from a short holiday & we went to York for a looong weekend. First on the list of places to visit was the National Railway Museum which is a sort of ‘branch line’ of the Science Museum. This was excellent. Lots of “Ooh, Aah'ing” at massive steam locos and getting nostalgic & middle-aged at the sights of old railway trivia like tickets, etc. They had a cut-away steam loco – a southern region Navy class – with the wheels going round, etc, so you could see it working. This reminded me of the old models at the Science Museum where the wheels went around when you pressed the button! We also visited a Museum of Automata. This had various music boxes, clocks with fancy displays and mechanical dolls. It also had modern items. Some were from piers & seaside arcades & showed various ‘naughty’ scenes. There were also some modern items built by Toby whatever (he helps Tim Hunkin with models for the Channel 4 TV Secret life of... series). These were great fun.

Other visits included the local Theatre Royal and various eating establishments. The best of these were a Sardinian restaurant recommended by our landlady and a vegetarian one we found in a back alley. This place was decorated in an arty-pretentious style & reminded me a bit of Tony Hancock as the self-serious artist. but the food was good. We also ate a few times in Betty's which is apparently a world famous teashop. I suspect this is on the basis that ‘world = Yorkshire’, but it was very good, although expensive. Our B&B was very good. We recommend it if you haven't been to York. York itself is very interesting. Lots of old buildings and winding (or do I mean windy?) streets. And lots of tourists and cars! They ban cars from the central old & shopping parts, but it can be a nightmare crossing the roads that go around this central section. Having provided a pedestrian area the powers-that-be don't seem to have realised that said pedestrians have to get to and from the central area without being mown down! I enjoyed the York art gallery. It's small, but has a decent selection of paintings. They had an exhibition on of quilts, but these were pretty pathetic compared with the paintings. Being in there also prompted me to buy a book of Dufy prints which I liked. The only bad experience in York was with a faulty Barclays Bank machine which ate my cash card & refused to release it. Naturally, this happened on a Sunday morning. I 'phoned Barclays to warn them that the machine was faulty, but they couldn't give a hoot — didn't even apologise. Their assumption was that it must be my fault. I left Chris by the machine while I rushed off to phone since I was worried that the card would pop out again once we'd left. Fortunately, a pair of street theatre people turned up in the square in front of her so she was able to watch their act along with a crowd while waiting. (We went back to the bank on Monday morning & the machine was “out of service” because of the fault. I wonder how many people's cards it ate before anyone actually did anything...) My own bank were very helpful & stopped my cashcard immediately.” |

1993 Sept. Essex Conference - Bifurcations in Gunn oscillator output |

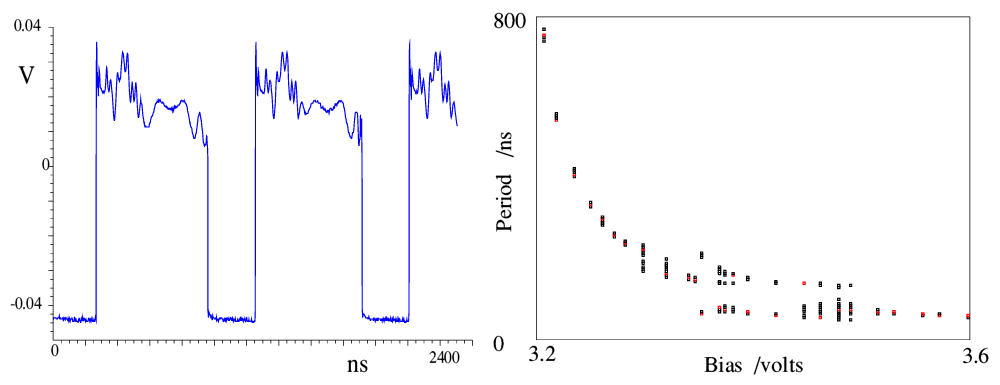

A conference on MM-Wave topics took place at Essex University in September 1993. It had been organised by Terry Parker and Jim Birch. I’d arranged that I would attend, along with Malcolm Robertson and Graham Smith, and that we would present two talks/papers. One of these was authored by Duncan Robertson, Graham, and me, plus Nigel Couch and Mike Kearney of GEC. The graphs shown above illustrate the results we’d obtained by using Gunn diodes in waveguide mounts arranged to operate in a pulsed mode. The results indicated that the oscillators were able to operate in a ‘semi-chaotic’ way. This was significant from our point of view as such oscillators might be useful for applications in cryptographic communications, etc.

1993 Sept. Essex Conf. Spatial Interferometry |

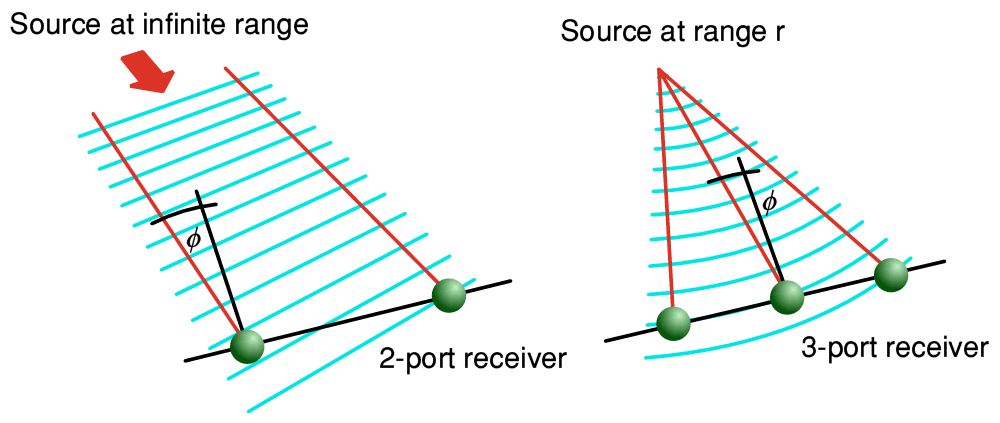

The second talk was authored by Malcolm Robertson and myself. This was on the topic of spatial interferometry. During the 1990s the design and use of 2-port and 3-port spatial interferometry became one of the main areas of interest of the MM-Wave group. In essence it operates on the basis of comparing the times of arrival (or phases) of portions of a radiated signal arriving at two or more places (ports). By using two ports it becomes possible to detect the direction of arrival of a radiated signal. Using three permits the radius of curvature of an arriving wavefront to also be measured. Thus a 2-port can tell you the direction a signal came from. And a 3-port can tell you how far away the source must be. The initial work on this topic had been funded by the Defence Research Agency at Funtington.

People are generally familiar with the use of RADAR to determine the distance and direction of something. However this requires the RADAR to emit signals and then look for reflections. Whereas the systems here can determine bearing and range passively. i.e. they can operate using signals radiated by the object whose range and bearing you wish to determine. This can include thermal radiation from a distant source. The talk/paper for the Essex conference showed the results of our analysis of what should be possible using such a thermal, passive 3-port for detecting and ranging.

Unfortunately, although I’d planned and arranged that three of us would attend, by the time of the actual conference I felt unable to go. This was a problem for Malcolm as he at the time knew far less about the spatial interferometry systems than myself. The intent had been that I’d present the paper and then answer any questions. But since I felt unable to travel, this had to be left for him, and he wasn’t really prepared for this. It may seem strange that I felt like this having so recently enjoyed the trip to York with Chris. However there were two significant differences between that trip and this one. Firstly, Chris and I had gone together to York, and stayed together when there. Secondly, at that time she had been feeling OK. Whereas the Essex conference would require me to either leave her by herself in St Andrews, or be away from her most of the time at the conference even if she came to Essex. And since York she’d had another episode of feeling unwell. So I was unable to control the anxiety about being leaving her by herself. Anxiety also tends to lead to a ‘negative feedback’ effect. For me this took the form of becoming anxious over if I’d manage to travel or not, and that anxiety making me feel unwell, and thus unable to travel! Yet I knew my attending would be helpful for my work, and to support Malcolm and the rest of the mm-wave group.

This was a particularly upsetting example of the effects of my anxiety attacks at the time. Malcolm did go and presented the talk, but then, quite understandably, was unable to fully answer every questions. All he could do was apologise that I was unwell. I have wondered since if this also meant others at the conference didn’t really understand what I wished to explain at the time, so didn’t realise the full implications of what the methods described could achieve. Fortunately, the approach proved successful when use used it.

During this period Chris and I both saw a number of advisers, therapists, etc, in the hope they would help. In some ways they did allow us to release some of the upset and stress we both felt. But the real difficulty was that during those year no-one – including Chris or myself – really understood the root causes of the problems we had. So we were chasing symptoms assuming that one symptom or another was the ‘cause’ when this wasn’t actually the case. Chris’s periods of depression tended to become deeper and longer, and I became more anxious about how to cope when with her... and what she might do when I was not. This situation continued to deteriorate throughout the 1990s.

In October I got a letter from HMRC (Income Tax) saying that I had received an ‘undeclared’ payment for an unstated amount and asked me to explain this. It was what I can best describe as a ‘fishing’ letter because it said nothing about any details. In essence the HMRC Inspector was trying to find out what income I may have had without declaring it for tax purposes. I was actually baffled by the letter as I couldn’t initially think what might be referred to. So I wrote back asking for some details to help me recognise what was meant. To the best of my knowledge I had declared all the payments I’d received for things like magazine articles, etc, and hadn’t omitted anything that needed declaring.

The reply made me realise the HMRC were referring to the money I had been given by the NPL as an award for the second National Metrology Prize I’d got during 1992. So I wrote back to the HMRC explaining that this sum was one I’d been told by the NPL was not taxable because it was a ’prize’. not earned income. I also pointed out that I’d received a similar award a few years before, on the same basis. (Which presumably the HMRC had not noticed at all.) I then worried that what I’d been told by the NPL was wrong! Fortunately, the Tax Inspector wrote back and confirmed that the money was, indeed, not taxable.

1993 Oct Nature - Chaos in Harness |

Towards the end of 1993 one of the editors at the academic science journal, ‘Nature’, contacted me. They invited me to write a brief item about the work I and the St Andrews group were doing on ‘chaotic’ oscillators and their possible uses. A short item I wrote on the topic duly appeared in their issue dated 14th October 1993. The idea behind this was to use wideband oscillators operating in a circuit/bias situation that produced a waveform pattern characteristic of a large – but finite – number of ‘bifurcations’.

The result was that it’s output looked like ‘noise’ when examined over a ‘short’ period, but would repeat after a sufficiently ‘long’ time had elapsed. Some of the Gunn and multiple barrier devices we had tested would, in this situation, output a signal with a self-modulated bandwidth well over 1 GHz and for most purposes the output did, indeed, just look like noise. However if the bias/circuit arrangement was altered by a slight amount the behaviour could be changed to that characteristic of a slightly different number of bifurcations. i.e. The output still looked like noise, but had a different underlaying coherent pattern.

The idea was that to receive this, a similar circuit could be set up to operate in a similar way. One oscillator acted as a ‘transmitter’ and an attenuated version of its output could be injected into the second ‘receiving’ oscillator. This then would ‘injection lock’ – i.e. latch onto the pattern coming from the ‘transmitter’. i.e. This would tend to ‘nudge’ the receiving circuit so it would then lock on to the transmitted pattern, and its operating behaviour would shift accordingly. e.g. its bias current would alter to a value indicating which of the number of bifurcations were in use. Thus although the transmitted pattern always seemed to an innocent bystander to be ‘noise’, the ‘receiver’ could be used to indicate what number of bifurcations the ‘transmitter’ had been set to operate under. These various states could then be used as ‘symbols’ to convey information via a signal that – for all other observers, appeared to be low level wideband noise.

The obvious use of this method is cryptographic communications where the receiver need a ‘key’ to understand what information is being transmitted. And in this case the key is a physical one – a specific kind of diode or other electronic device, in a specific circuit, etc. However having been working on this I realised it had the potential for providing steganographic communications. The term ‘steganography’ is less well known that ‘cryptography’. It means that the very existence of a message is ‘hidden’. i.e. the aim isn’t simply to hide the meaning of a message, but to arrange that no-one other than the intended receivers should even realise a message is being sent! This adds another layer of security to the information involved, and also helps protect the location or identity of the transmitter!

By the end of 1993 Duncan Robertson and myself were starting to carry out work for Roger Appleby and Johnathan Borrill of the Defence Research Agency at Malvern on some potential applications of this idea, combined with the use of 2-port and 3-port spatial interferometers. This work built on the previous research carried out by Malcolm, and was directed at novel ways to determine the direction and range of signal sources by ‘passive’ means. e.g. to provide the direction and range information which radar might conventionally be used to obtain, but without having to transmit anything at the target. Thus avoid the target knowing its position had been sensed, or revealing that someone had done this. For obvious reasons, this ability would be particularly useful on a battlefield.

Given my increasing interest in spatial interferometry, I was quite happy for Graham and Peter Riedi to focus on the ESR system while I worked on the areas related to defence research and development. Hence by the end of November 1993 I was sending quotations and descriptions to Roger for our building some mm-wave Quasi-Optical frequency discriminations and spatial interferometers, optimised to operate in the 90 - 120 GHz region. (The main factor that had to be optimised was the anti-reflection pattern of grooves on the lenses. By default, this tended to be targetted at getting best performance at 94GHz, but the systems could work well over a wide range of frequencies.)

During December we were told that DRA Funtington’s funding had been severely cut, and this impacted on their support for Malcolm Robertson. His income from them would hence end early in 1994. So I started some discussions with Wilson Sibbett (Head of the Physics Dept.) about alternatives for Malcolm. Sadly, at the start of December Jim Birch also phoned me to say that his entire research and development sub-division at the NPL was now likely to be closed down! This was a result of a new “bean counter’s rule” that only work directly requested by industry should take place. Sadly, the NPL work was eventually closed down and Jim Birch eventually retired from the NPL.

I was at the time also discussing other arrangements with Wilson. These arose out of the departure of Ian Firth who had been a lecturer specialising in the measurement and design of musical instruments. I’d been asked to take on some of his old responsibilities, which of course meant more work. But in exchange I was ‘given’ his old research equipment and – much more interesting from my point of view - a small anechoic chamber which he used when making audio measurements. I was still interested in Hi-Fi and audio so I welcomed this, and some extra bits of equipment Wilson agreed to the department buying for me.

In February 1994 I wrote a ‘Leave Report’ summarising the use I’d been able to make of being given two sabbatical terms – one in 1992, the second in 1993. These had provided me with extended periods where I was able to focus on building up the group’s research and thus increase the departmental income and reputation. In theory, such sabbatical ‘leaves’ were at the time meant to occur every few years when appropriate. But I hadn’t applied for any until 1991. (The snag was that although they let me not do any lecturing, etc, during those terms, I had to give the lectures I’d ‘missed’ in one of the other terms each year! So my total teaching load wasn’t actually any less, just shuffled into more intense bursts.)

I was able to report that the sabbaticals had aided me in bringing in new SERC grants, income from other sources, producing various publications, books, etc. So they had clearly been worthwhile. In addition to the SERC grant in conjunction with Peter Riedi we had obtained another in conjunction with Wilson Sibbett which was employing Malcolm Robertson to work on possible THz sources driven by a pulsed laser. I’d also at that point just been told I’d been given another grant to push forward development of THz ferrite devices – and area of work that had been started by Mike Webb during his time with us before he returned to Australia. Duncan Robertson had also been funded by the DRA once his studentship had ended. So overall, the research situation for the group was very healthy.

In February I unexpectedly received a copy of the Barbirolli Society Journal along with a letter from David Li Jones. I’d not had any reply to the letter I’d sent to Pauline Pickering many months before, so had given up hope of making contact with the Society. I immediately sent David a cheque as my membership fee to join the Society, and remain one even now.

In February I also received a letter from Derek Martin, inviting me to attend the special event commemorating his work on the occasion of his official retirement. I wrote back:

|

“Dear Derek, Thanks for your letter of 22nd Feb. Yes, I'd be delighted to come to the meeting and attend a dinner. (And Chris says “me too” to the dinner, if that's OK!) However, I'd like to direct my talk towards some of the new applications of THz/MMW Quasi-Optics... I have mixed feeling about your retirement. I tend to think of you as the “main tent pole” holding up the big top over the whole mmw/THz circus! I hope your retirement doesn't mean that the canvas will drop down on the rest of us – leaving us struggling in the dark... That said, the field seems very healthy at the moment. The York meeting last year seems to have made SERC much more receptive to THz ideas (at last!) A while ago I was stunned to find that we'd just been awarded our third SERC grant application in a row. I had to have a cup of coffee to help convince myself I wasn't dreaming. Quite a turn-around from the mid-eighties when SERC wouldn't give me the time of day and I had to rely on the NPL.” |

During the first years of my working at St Andrews University the bulk of the MM-Wave Group’s research funding came from the NPL and other sources and people I’d known from my time at QMC working for Derek Martin. This had then expanded via contacts in industry (at EEV, GEC, etc) and into defence research organisations like DERA or facilities like JET. For some years I’d found it almost impossible to obtain a grant from the UK’s science research councils. However by the mid 1990s things were changing.

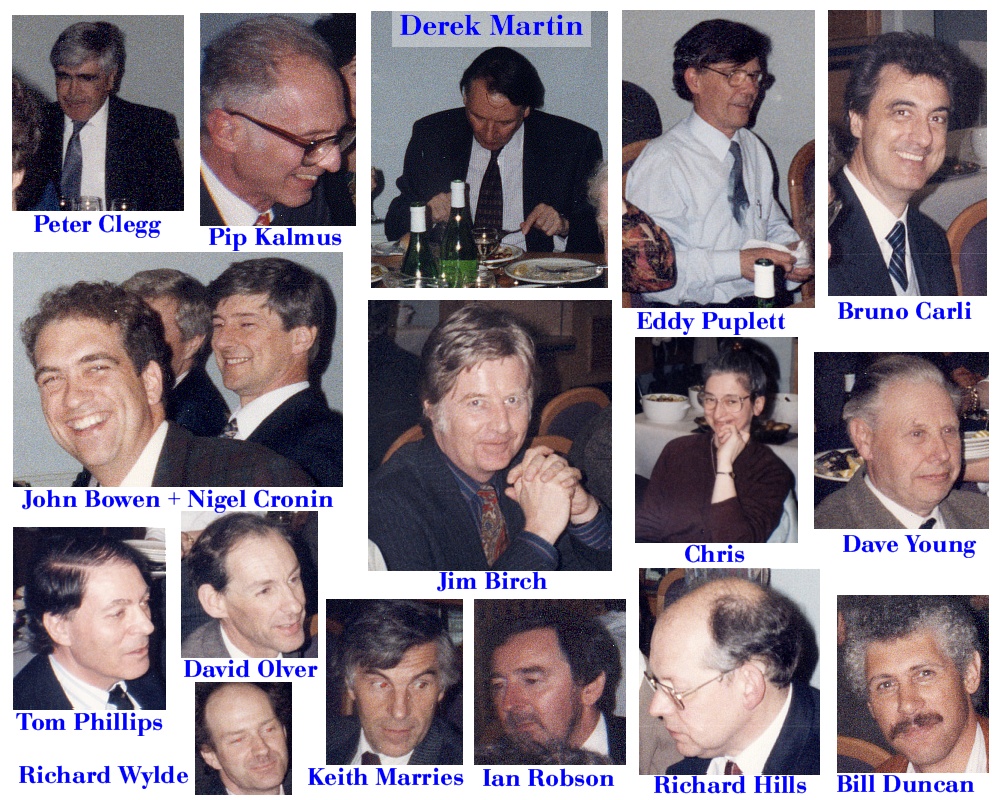

1994 May - Derek Martin’s retirement dinner |

Derek officially retired in May 1994. The special event was organised to mark the retirement. It gave us a chance to show our appreciation for his work and the help he had given to us. Many of his ex-research students and co-workers attended. During the day we took over the main lecture theatre in the QMC (by then QMWC) Physics dept., and gave a series of short talks summarising how his work had lead to developments he had inspired or aided. It gave me, and many others, a chance to thank him in public for what he had done for us, and for the mm-wave area of science in the UK. We also gathered to present him with a glass bowl which had been inscribed with a series of messages we had arranged to be cut into it. (If anyone now sees that bowl, the item I had added was a short equation which is used as a basis for Gaussian Beam Mode calculations!) We also held a celebration/thank you dinner for Derek. In between courses at the dinner I took a set of photos, and the above illustration shows many of those who attended. This was an end of an era. Derek did continue to do part time and consultancy work, but as can be expected this gradually reduced over the following years. But he remains fondly remembered by those who had the privilidge of working for or with him. He was a genuine friend as well as an outstanding academic.

The other large change during this period was at the NPL. The UK Government in its infinite (or do I mean infinitesimal?) wisdom pressed forwards with the changes it wanted at the NPL. This was bad news for many at the NPL. It also meant that it would become almost impossible to obtain funding from them to develop entirely novel measurement systems which might be urgently needed, say, a decade later, but weren’t currently demanded by UK industry. The clear outcome was that the kind of funding and development I’d been fortunate enough to obtain during my early years at St Andrews was to be cut away. Fortunately, by this time I was finally becoming successful at gaining research council grants, and money from defence and industry. So the MM-Wave Group could find funding. But if these changes had happened a few years sooner the situation for my area research would have been bleak. What negative effects this had on others who were less fortunate than myself, I can only guess.

During April, Chris made contact with the “Express Group”. This (and I think still is) self-described as a ‘self help group’ for people with mental problems. She’d read about them in The Citizen, inviting people to become volunteer helpers. Chris then went to a few meetings of the local group. Her original intent was to find out more about them and determine if she could help or be involved in some way, given her experience as someone with a history of mental illness, epilepsy, etc, and from her work many years before in London with the British Epilepsy Association and the NHS’s Health Council for the area.

Then, one week, she had a major fit whilst at the group meeting. The following week she was told they did not want her to become a volunteer helper. So far as she could see, this was solely due to her having epilepsy – despite one of the claimed points of the group being the ‘self help’ which people with mental issues could provide for each other on the basis of personal experience. The episode highlighted in her mind a basic contradiction in the publicity statements the group made at that time. One the one hand it said they were a ‘self help’ group – the point being that those who knew about the problems from experiencing them were best placed to understand and provide ways to deal with them. On the other, the ‘volunteer helpers’ who – it seemed - had to be people who didn’t have the personal experience. This seemed to divide those involved into two categories.

Chris felt very strongly that their unwillingness to let her help showed they had needless fears of an all-too-common kind about epilepsy. I wasn’t present at the meetings, but given her many years of experience with the CAB, and other work in previous years I knew full well she was quite capable of acting as a volunteer helper for people with serious problems. Particularly when they were of a type she was familiar with from personal experience. What upset Chris was that the group were reluctant to even discuss the matter with her.

On the 23rd of May I wrote a letter of recommendation to support Graham applying for the position as a Lecturer in ‘Photonics’ in the St Andrews Physics Dept. Usually ‘photonics’ tended to be assumed to mean working with visible or near-visible light. But I used to argue that at mm-wave we had many more photons per Watt than you’d get in the visible, so the mm-wave work was clearly ‘photonics’, and – of course – our instruments tended to use optics... I started the letter by saying that:

“Reference for Graham Smith re. position as a lecturer in ‘Photonic Science’.

I then went on to outline his strong track record and make clear that the ESR system he and Peter were developing was expected to become regarded as a National Facility in demand by researchers from many other places. |

During July I sent the final draft of my third book, on Information and Measurement, off to the Institute of Physics press. This was an undergraduate level textbook that deliberately took an unusual approach which I felt (and still think) gives a better path to understanding the topics for scientists and engineers than is usual for books on information theory. Although long out of print, I recovered the rights and have since made a free Adobe PDF version available for anyone who wishes to download and read the book. (You can use this link to download a copy if you wish to read it.)

By this time the main focus of my own research was working with Duncan Robertson on the topics of spatial interferometry as a passive alternative to radar. In particular, considering this in terms of its applications in defence. As a result we were doing a lot of detailed analysis and designing/testing systems, supported by DRA Malvern. A preliminary spatial interferometer system had been built and we made two trips to Malvern during 1994 to set this up and demonstrate it to various people.

Professor Arthur Maitland died at the end of July 1994. This was a great loss to the department as well as for his family. Arthur and I had always got on well together as we had a similar approach to research, with a leaning towards finding industrial or other ‘real world’ applications – and funding – for devices or instruments we could devise. I recall the stories of how he might work on a system powered by high voltages by wearing wellington boots and rubber gloves so he could adjust it as it continued to operate. And the ‘anti-clockwise clock’ he had on his office wall. When on occasion he wanted so see me, I’d join him asking, “What can I do you for?” as a joke about our common interest in finding clients willing to pay for research. We also shared an interest in defence applications as well as industrial civil ones. He played a big part in giving the department some human character, and making it more than simply a place to work.

Wilson Sibbett’s period as Chairman of the Department was coming to an end, and on 25th August I wrote to the Principal urging that the next head to be appointed should be Malcolm Dunn. He had originally worked for and with Arthur and had since built up his own successful research group. In my view he was the best possible candidate to take over from Wilson, and was duly appointed at the end of the selection process to become the next Chairman.

Order of service for Arthur’s Memorial in September |

At about the time of Arthur Maitland’s Memorial Service I was surprised to be asked to take on some of his postdoctoral research workers and one of his PhD students! Although I was similar to Arthur in doing work for various DRA establishments, our areas of research were fairly different, so I hadn’t occurred to me that this might happen. I’d assumed they would have been taken over by either Malcolm Dunn – who had initially worked for Arthur – or by another lecturer, Chris Little, who had worked with him up until his death. However I was contacted by Wilson Sibbett and visited by Natalie Ridge, Peter Hirst, and Ewan Findlay who asked me to become their supervisor.

Having discussed this with them, and establishing that their DRA sponsors and the head of department were happy for me to do so, I agreed. However Chris Little was clearly not happy about this and I was given the impression that he had taken for granted that he would take over Arthur’s group, lock, stock, and barrel, but the members of the group felt differently. As a result Chris asked to see me to discuss the situation.

At the time he had arranged his room so that his desk was under his office window, with it behind him when he spoke to visitors. As a result, the chair for visitor had them sitting down looking into the bright light. Because of this, and my eyesight being poor, I avoided sitting in the chair and sat on the corner of his desk, instead, so I would not be dazzled by the light when trying to look at him. When he made clear that he felt he should be the supervisor, not me, I explained that I was only accepting the role because I had been asked to do so. Hence, rather than argue with me about it, he should convince the people to be supervised. If they agreed, I’d be happy for him to supervise them. But if they and Wilson wanted me to be their supervisor I was content to take that role to help them out. As result, they worked with me as their supervisor for the following few years.

A sting in the tail of this particular development occurred a few years later when Chris Little left the St Andrews department and returned to Australia to take up a post there. When he left he told one DRA establishment that we had a ‘document controlled’ filing cabinet with unspecified contents. These are lockable secure filing cabinets used to hold ‘classified’ documents. Arthur had one because of some of the work he and his group had been doing. The snag was that we had no officially designated ‘document control officer’ of the kind a DRA, etc, would have to be responsible for the content. And if there were any classified items in the cabinet anyone opening it would need the required clearance to do so! By this time Malcolm Dunn was head of the department, so we both had some discussions with the DRA people concerned and it was agreed that he and I had the required clearance. We duly opened the filing cabinet, checked the contents, then destroyed them. In practice, there was nothing of any significance in the cabinet, but we went though the relevant rigamarole to be able to confirm this.

The above was something of a farce because everyone involved knew from the start that the cabinet wasn’t going to hold any significant documents. Less amusing was an abrupt announcement by the central organisation of the University that it would now impose a “100% overheads” requirement on all contracts. I’d been cheerfully adding overheads to our contract, quotes, and prices of items like oscillators for years. So I had no objection to this, per se, and it had baffled me that for many years the University didn’t seem to really understand how overheads are used in general business. However, astonishingly, they announced this would apply retrospectively to all existing contracts! This was best described as ‘insane’ as a policy for an obvious reason: Those contracts had already been costed and signed. So we could not legally tell the clients they had to pay this new amount given that it was higher than we’d previously, legally, agreed to. The University lacked the required magic wand to make this happen.

Thus the only way the University centrally could take this new amount would be to remove it from the sums agreed for employing the staff, buying the requires consumables, etc, etc. Given that our contracts all tended to be based on some physical ‘deliverable’ – e.g. an oscillator or a quasi-optical circuit – which had to work as specified and be delivered in the agreed timescale meant it would be stealing the money from the amounts set aside to do the work. As a result it was an action likely to cause the project to fail to deliver. Which meant the client could ask then for all their money back, and possibly also for recompense for the effects upon them of the failure. Likely also to lead to no-one ever wanting to pay for any kind of contract work again. Overall, it would be a spectacular own goal by the University in terms of its effect on bringing in cash, and damaging for our reputation.

This was an example of how clueless some of those in charge of running University were at the time of how real commercial business was done when based upon having to make something to do a specified task. Not just write an academic report musing about what might be possible. Some ‘discussions’ took place as I, and others in the Physics dept., ‘enlightened’ those who had issued this edict about it’s folly. Having seen sense, the retrospective element was duly abandoned. But it was astonishing that anyone thought it sensible in the first place.

By the end of 1994 what had been the MM-Wave Group now had three ‘divisions’. One for the mm-wave work, a second for Microwave Plasma Technology, and a new ‘Audio’ section having acquired the anechoic chamber. In addition to Malcolm Robertson, Graham Smith, and Duncan Robertson, there were four new postdoctoral workers – Sarah Kang, Ewan Findlay, Natalie Ridge, and Peter Hirst. Plus Ian Dennis, working in the audio area, and Charles Unsworth, working on mm-wave items, as PhD students. The group overall was now large and well established. So we ended the 1992-4 period in a better state than we had started, despite the sad events which took place.

11,000 Words

6th April 2019

Jim Lesurf